Already sizeable and growing, Seattle Indian Health Board’s workforce is filled not only with talent but also an array of lives, journeys, and wisdom. Relative to Relative is a conversation series, lowering barriers to connection through unscripted storytelling. Each installment is an invitation to weave new relationships and recognize the humans behind our healthcare.

In the basement of the International District Clinic, there are probably a few pests, but they are undoubtedly outnumbered by the plastic spiders surrounding Marty Schafer’s desk. A desktop support specialist in Seattle Indian Health Board’s IT department, Marty (Cree) spends a lot of time detangling the web of devices that connect our staff and squashing the bugs they catch.

“Everybody hates spiders,” said Schafer, cradling one in his palm. “They help me. Computers get bugs in them, and you know, people say they’re software bugs, but spiders are really good at getting rid of them. So, I’m the spider man, and I fix things with my little spider friends.”

As a general rule, Schafer is happiest when surrounded by creatures. Though he’ll always consider his birthplace of Calgary, Alberta home, Marty knew he’d found his current home-away-from-home on Vashon Island when he was first greeted by the land’s wildlife.

“I took a drive out to Vashon Island, and I had a little dilapidated Volkswagen Rabbit with a sunroof,” he said. “I’m driving along going, ‘Boy this this looks familiar, this looks like those dreams I had,’ and I look up and there’s a bald eagle about six feet above the opening of the roof, flying along slowly and looking down in at me.”

After alerting his then-girlfriend now-wife to the eagle’s presence, Schafer had to break for a family of geese crossing the road. In that moment, he turned to his partner and said, “I need to live here.”

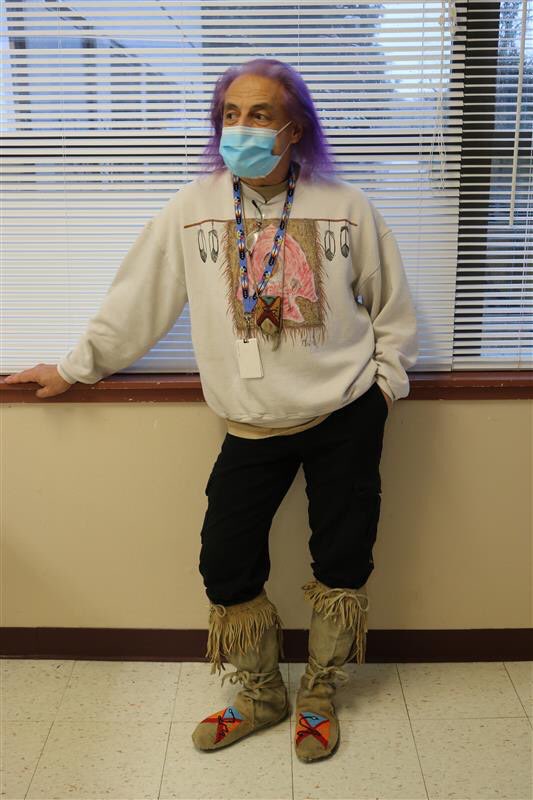

Since then, the pair have built a very joyful, very purple life for themselves on the island. Everything, from their house’s exterior to that old Volkswagen to Schafer’s own hair, is bright purple. The rationale behind the color scheme is sweet and simple: happy wife, happy life.

“I think the reason my hair turned purple is because it’s my wife’s favorite color,” Schafer explained. “And my body knew if she was going to keep me around, I’d better be purple. And well, there it changed!”

His path to working in IT and eventually for SIHB was less direct. Prior to settling into a technology-centered career, Schafer made ends meet in the arts: crafting moccasins and beadwork, acting in local theater productions, even appearing in a 2006 limited TV series Northern Lights.

Eventually, a lifelong aptitude for machines and the sheer abundance of jobs available in IT led him to decades of work as a support specialist. And while he’s always enjoyed the work, Schafer hasn’t always loved the companies he’s worked for, put off by the dubious ethics of the larger tech industry.

That changed with SIHB. Though he’d never intended to work in healthcare, Schafer was drawn in by the idea of a Native-led, culturally attuned workplace. As a result of his mother’s traumatic forced entry into the foster care system, he’d spent the bulk of his early life disconnected from his own Indigeneity.

“She didn’t want to talk about it,” he said. “We knew we had Native relatives. We’d go see them every once in a while, but it was really never…Mom had kind of escaped [the system], and that was what you had to do back then.”

On his first walk-through of the organization, Schafer was struck by the “bubbly, magnetic” personalities of the staff he met. Something essential had finally clicked.

“This is it,” he said. “This is family. This is where I’m supposed to be. This is where I was always supposed to be. I just didn’t know.”

Joining SIHB’s family has not only given Schafer space to reconnect with culture but also filled his mother with immense gratification.

“She is so proud of where I’m working now,” he said. “She’s got my business card framed on the wall.”

For Schafer, that sense of connectedness extends well beyond the clinic’s walls. Everyone is a relative, after all, and it is Marty’s personal mission to connect with every person he encounters. One of his most meaningful experiences as an SIHB employee happened during his nightly commute through downtown.

“I’m walking down the street and this man says, ‘Sir! Sir!’ and he says, ‘I gotta thank you!’”

Caught off guard, Schafer asked the stranger what he could possibly have to thank him for.

“Gettin’ me healthy,” the man replied. “You told me not to be sick and to go to your clinic, so I went down there, and they fixed up my leg, and I’m getting my COVID shot, and they’ve got me on some plans to get me healthy. I gotta thank you! It’s not costing me anything.”

Marty nearly danced on the way home after that. It is a rare treat for a behind-the-scenes, literally underground staffer to witness their own impact firsthand.

Knowing a small conversation with a stranger could make that big of a difference, that seeing one life undeniably changed is enough reason to keep chatting—those are the sparks that stoke the fire within one of SIHB’s most talkative tricksters.